28 years of pioneering paths for those with developmental disabilities

Preston, Idaho

May 2025

When I sat down to talk with Rhonda Phillips, director of the Developmental Disabilities Agency at Franklin County Medical Center, I expected to learn about a disabilities program. Instead, I left with a powerful story of resilience, advocacy, and love—one that has shaped generations.

Rhonda Phillips grew up in Fairview, Idaho, a small town just outside of Preston. Preston is well-known as the filming location for the 2004 comedic film, Napoleon Dynamite. Prior to moving my own family to Preston three years ago, we began watching this movie but couldn’t finish it. The exaggerated depiction of small-town quirks and portrayals of insular culture left us feeling uncertain about the community we were moving to. However, after we arrived, and I started meeting people like Rhonda, those misgivings melted away.

Upon starting my new job at Franklin County Medical Center in Preston, I was particularly intrigued by one program—the Developmental Disabilities Agency, or DDA. The DDA is a state-sponsored program which the hospital owns and operates. As I tried to orient myself to my new job, I asked Rhonda, “What is the DDA?” She beamed. “Oh, it’s just so exciting!”

She then provided a simple dissertation on the program, and her passion and wisdom became apparent. As she spoke, I noticed a picture on the wall—a picture of two sons, both with disabilities. Fighting to retain what I could from the onslaught of a new job, I managed to recall this important fact: the program and its director were remarkable.

Rhonda's two sons Paul (left) and Patrick (Right).

Rhonda's two sons Paul (left) and Patrick (Right).

Rhonda Phillips, director of the DDA

Rhonda Phillips, director of the DDA

Now, three years later, I have a deeper understanding of the Developmental Disabilities Agency. With Rhonda’s guidance, I can better explain how it operates. The program supports individuals of all ages with developmental disabilities by helping them integrate into their communities. It also provides caregivers with resources, training, and—perhaps most importantly—a strong support system. A passionate, highly trained staff works with clients and families to build skills and encourage positive behaviors—while having loads of fun.

Though the program was officially started one year earlier, Rhonda took the helm in 1997. Back then, the program was what Rhonda comically, but tenderly, described as “one client and a milk crate.” At the time, all of the tools and materials she had fit in that crate.

“We had everything we owned in that milk crate,” she said. “Like we had some games, we had some fine motor activities, and we would go over to the nursing home and we would say, ‘What room’s available?’ And they would say, ‘Okay, you can be in room six today.’ And we would take our clients and go to that room, and that’s where we would do services.”

Rhonda has an unorthodox education supporting her role in the DDA. She completed her bachelor’s degree at Utah State University. When she told me it was a bachelor’s degree in dance, I was surprised. Having a psychology minor myself, her technical knowledge as a behaviorist was easily recognized. This is where Rhonda explained, “My degree is actually my two boys.”

When Rhonda gave birth to her second child, Patrick, at the hospital in Logan, Utah, she was told he had Down syndrome. “Back then, it was a total surprise—there was no way of knowing. But we were ecstatic,” Rhonda told me.

The doctors thought she and her husband were in denial. At delivery, and in three subsequent surgeries, the medical staff recommended Rhonda institutionalize Patrick. Taken aback by this suggestion, her response was an emphatic “No.”

Disbelieving her initial response, I pressed Rhonda for more explanation. “You were excited, even at first?” She clarified, “Oh, yes—but only because we were already working with kids with disabilities when Patrick was born.”

During a summer in college, Rhonda’s then-husband found a job driving young people with disabilities to the Cache Workshop in Logan, Utah—a vocational program where they earned pay for their work. “My husband said, ‘You’ve got to come with me when I drive—it is awesome,’” she recalled. Rhonda joined him on a drive and loved it.

Without that experience, Rhonda said, “I’m sure I would not have taken the news as well.” Even before Patrick was born, she remembers hoping she might one day have “the privilege” of having someone with disabilities in her family. That hope was realized—and it sparked a path that would go on to intersect with and support countless families through her work at the DDA and in the broader community.

Rhonda raised Patrick just like she raised her seven other children. She explained, “The only difference is that sometimes when a person with a certain disability wants to tell you something or has an unmet need, they don’t always know how to communicate it. So when he was young, I would tell Patrick's friends that if he behaved in a certain way, it wasn’t aggression—he’s just learning to communicate.” She continued, “The kids got it. They would take to it right away. It was adults who had a harder time understanding.”

“Every person is an individual, so of course, no two people with a certain disability are the same.” This is a truth Rhonda both believed and experienced as she adopted her youngest son, Paul, who, like Patrick, was born with Down syndrome but also has autism. She said, “Patrick is a people pleaser. He loves people, and they love him. Paul is the complete opposite.”

Rhonda described being a bit naive to the realities of behavior extremes that can come with cognitive disabilities. She fondly recalled how difficult rearing Paul was as a child.

“He would scratch my neck,” she said, chuckling warmly. “If ever he saw me lose my balance, he’d come and push me over.”

“Probably not so positive at the time”, I said.

“No, not so positive at the time. At one point, I was like, 'I just don’t know if we can keep doing this.’ It got that difficult.” Still, Rhonda knew this wasn’t Paul’s or her fault; it was just a combination of personality, Paul’s health problems, and frustration over communication barriers.

Paul’s unique needs exceeded Rhonda’s skill set, and she realized she needed help from a behaviorist. At the time, her family was living in Utah, and she was placed on a waitlist for six years before gaining access to state resources—even after receiving priority status due to incidents of physical harm. Eventually, she was connected with experts who developed what she called “a beautiful behavior plan.” But the plan was seven intensive pages long, based on a token economy system—and Rhonda was already raising seven other children while working. “I just said, there’s no way I can do this plan,” she admitted.

She had started work at the DDA around this time while completing additional college coursework, which ultimately exposed her to the theories and principles that emboldened her to put the seven pages aside and ink her own first behavior plan. I asked her, “What kept you going? I mean, why not throw in the towel?” Rhonda smiled, “He’s my son. I knew it from the minute I held him, he’s my boy.” This behavior plan was a breakthrough for her and Paul’s relationship and jump-started her success with other families at the DDA.

Behavior plans are at the heart of the agency’s work. Over the years, Rhonda’s team has onboarded and supported hundreds of families—each with their own unique circumstances. No two individuals or families are alike, but one thing remains constant: the behavior plan. Drawing on principles of behavior such as reinforcement, planned ignoring, and extinction—terms that may sound harsh but are simply technical language—interventionists craft personalized plans to help clients and their families reach their goals.

Rhonda leading 'Circle Time', a social skills building activity.

Rhonda leading 'Circle Time', a social skills building activity.

Wrestling with the concern that behavior plans might be dehumanizing, I asked Rhonda to help me see them in a different light. I had recently undergone hip surgery, so to explain the purpose of a behavior plan, she asked if I had used crutches afterward to support my mobility goals. “A behavior plan is not so different,” she said. “It's just an aid to help someone live their best life.” These plans—or interventions—can help with daily tasks like shopping, cooking, or cleaning, as well as skills like communication, managing sensory sensitivities, and fostering social connection.

The progress made by behavior plan recipients and their families is often profound. Sometimes, these plans create small but meaningful victories—like giving a parent 45 uninterrupted minutes to cook, a freedom they never had before. Recently, a parent began dropping off a young girl at the DDA who, at first, would kick, scream and bite the interventionists due to severe separation anxiety. Now, that same girl waves goodbye to her mom and blows kisses to the staff. “It works— it really works,” Rhonda said. “The only time it doesn’t work, and you feel like that as a parent, it’s because you don’t have a plan. But, it’s not a light switch, an overnight fix. It takes time, and it especially takes patience.”

Clients don’t always understand why they need to modify behavior, and boundaries can be difficult to set and enforce. Perseverance, building trust in the client-interventionist relationship and believing in plans are key. After a particularly hard day, one of Rhonda’s clients poignantly stated, “Tomorrow is another day. I will try again tomorrow.” That saying now lives on Rhonda’s bathroom mirror as a daily reminder.

The impact of these interventions is deeply felt. Paige Haslam’s 14-year-old son, Tye (pictured on the right), who has autism and is nonverbal, has participated in the DDA for more than eight years. “Our son has grown so much in so many ways,” Paige said. When Tye first started, he had no way to communicate his thoughts and feelings. Paige explained how the DDA taught him to use a communication device. Now, Tye can express his needs and emotions—like “I want to jump on the trampoline” or “I hurt”—by touching pictures that play corresponding audio messages.

He once refused to try any new foods, eating only Goldfish crackers and pepperoni. But with patient guidance from his team, he gradually learned to touch unfamiliar foods, then bring them to his lips, and eventually chew and swallow. Today, he’s willing to try almost anything.

Earlier on, as Paige sat in yet another drive-thru line at a fast food restaurant, she said she would see “so-called normal families eating in a restaurant and ask myself, ‘Why can’t we sit down and enjoy that time together?’” Tye was too uncomfortable in those situations.

Then Paige joyously explained, “Now, as a result of the DDA, we can sit down as a family in restaurants. He is a regular member of our family.” To help make social experiences like that happen, the team at the DDA takes Tye to places like grocery stores where he can buy an item and interact with people. He knows the DDA staff look after him and provide a sense of security.

DDA staff member taking clients to a grocery store.

DDA staff member taking clients to a grocery store.

A key aspect of the DDA’s program is social belonging—a basic human need that can be especially difficult to understand, or even receive, if you have a disability. The team at the DDA knows that this idea of social belonging is a key part of achieving goals and personal happiness. Each time I’ve visited the DDA, which is organized into two main groups of adults (18 and older) and children, I see the interventionists at work with their clients, but more impressively, I witness belonging.

I’ve dropped by during karaoke more than once, and while it’s a regular activity, the energy is always high. They always invite me to join, and though I politely decline—“I’m not any good” —, their inclusivity is inspiring. The agency also organizes a wide range of community activities, from bowling and dancing to agricultural experiences, like visiting a dairy, and participating in sports. This kind of social hub is essential. Without it, many clients would face significant barriers, including limited accessibility, lack of transportation, and social misunderstanding

Rhonda’s older son, Patrick, is a regular participant—and often leader—of these activities. He and the other members of the group decide what interests them and then work together to make it happen. Rhonda’s youngest son, Paul, on the other hand, does not participate. “Paul is not a people person, and just like anyone, you want to honor those aspects of personality,” Rhonda explained.

Glenda Elison, a parent of two boys who have received DDA services since its inception, said, “The DDA program gets my boys out in the community, out with friends. My boys know it’s a safe space for them, I know it is a safe space. They have a friend group and can do activities. They’d be home otherwise.”

A new parent to the program recently told Glenda, “My boy’s never had a birthday party, because he’s never had friends before.” Thanks to the DDA, her son has friends and a strong support system. Glenda credits Rhonda with being “the lynchpin that puts it all together for them” and says that our community should be proud of the work Rhonda has done.

But social belonging must extend beyond what the DDA alone can provide. The broader community also needs to embrace and include individuals with disabilities. Fortunately, Rhonda feels that Preston has done just that. She recalled a meaningful experience involving one of her son Patrick’s friends in high school. “The football team had one of Patrick’s friends, also with Down syndrome, on the roster,” she said. “During an assembly that celebrated clinching the state title, they presented his friend with a unique jersey. The student body roared in applause.” Patrick himself was crowned homecoming king, and he received an award in the senior assembly for being the friendliest person at the school.

Not everyone has been so kind and accepting. Without Rhonda’s pioneering efforts, her children—and many others—might have been denied the opportunities they deserved. Each time she enrolled her children in a new school, it was a battle. The buildings were often outdated and inaccessible, and staff would say things like, “Having them as students here would be impossible.” But Rhonda, along with other determined parents, fought to ensure their children had the same opportunities as everyone else. Sometimes, that even meant organizing new entryways or small construction projects to make inclusion possible.

When Patrick reached high school, the only place that would work as an accessible classroom was the space where the school convenience store was located. The principal didn’t want to make the change. Rhonda recalled, “The principal at the time told me, ‘You know these students are going to hate your kids for taking away their store.’” But after the football assembly, she boldly corrected him, saying, “Oh yes, they just sure hate my kids, don’t they?”

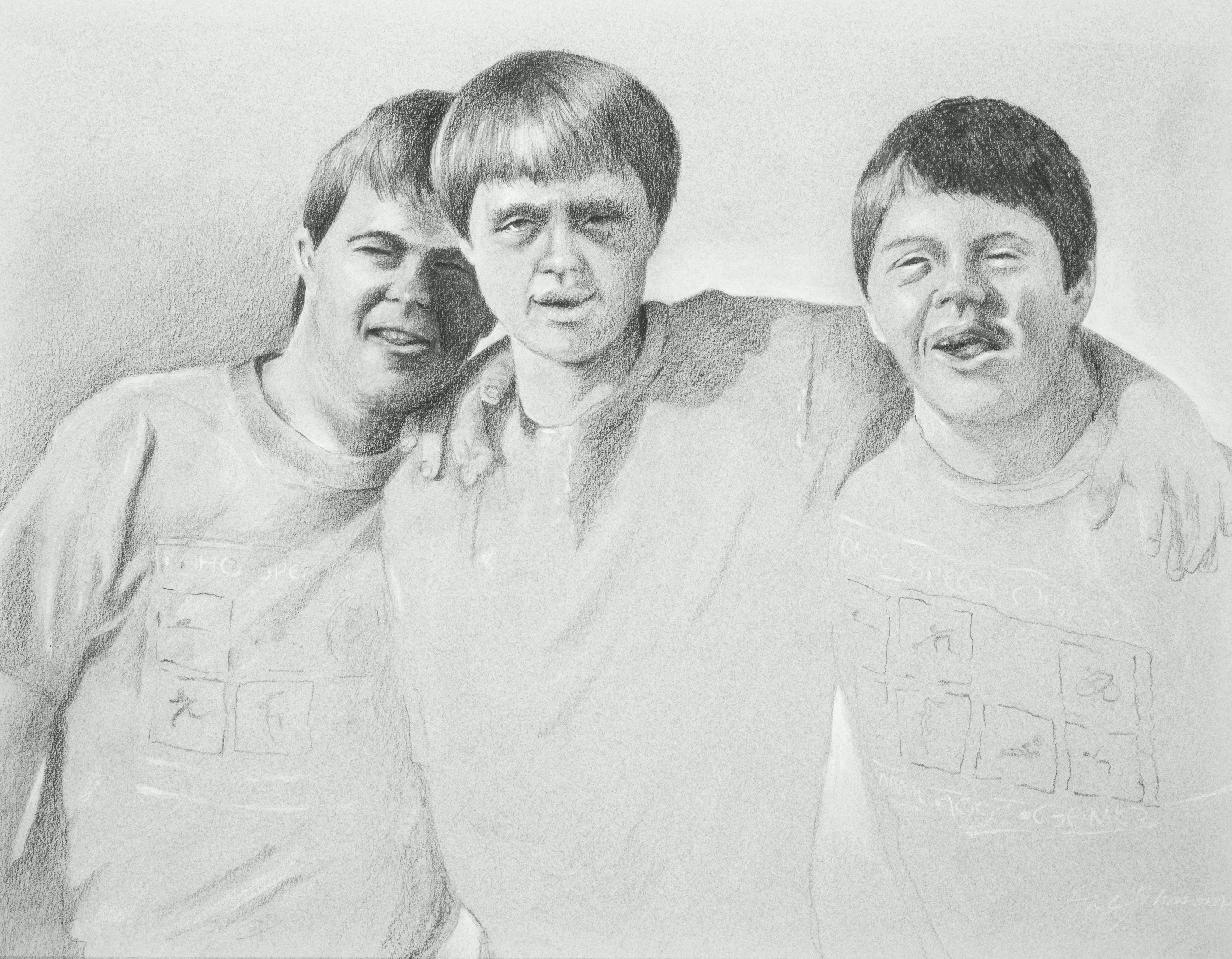

A local artist's drawing of Patrick and two friends in high school.

A local artist's drawing of Patrick and two friends in high school.

When Patrick was born, Rhonda ran into a good childhood friend. “She just didn’t really know how to act. It was like some bad thing had happened,” Rhonda said. She thinks society has gotten much better at embracing disabilities, but she still finds that among grown adults, disabilities can be awkward and frustrating. “It’s like there’s a wall, but once you break that wall you suddenly feel very comfortable.” I expressed. Agreeing, Rhonda said, “You have to break that wall, and then it’s gone forever.”

Sometimes people express pity, saying things like, “I just feel so bad they won’t have a normal life.” Rhonda sarcastically recounted, “Yes, they have such hard lives. My Patrick has been to Japan to compete in the Olympics. He’s flown on a leer jet with track star Florence Joyner (“Flo Jo”). He’s done so many wonderful things.” However, she does admit that without advocacy, it can be hard.

Rhonda preaches, “You have to choose to include,”. A truth made evident as she shares about how Patrick stayed with two of his brothers and other roommates at a college dorm. “Patrick was one of the guys. It only happened because that group of friends chose to include. Every year they have a reunion, and everyone really looks forward to it.” It means so much to Patrick.

One of Patrick’s brothers recently confessed to Rhonda, “I’ve just kept saying, ‘Why? Why can’t Patrick be like me, like the rest of us?’ All this time I’ve been wrong: I want to be more like Patrick.” Rhonda explained, “This son worries about everything. Patrick doesn’t worry about a thing. If someone is mean to him, he just will say, ‘Oh, he’s probably just having a bad day. I’m going to bring him a note of encouragement tomorrow.’”

Over Rhonda’s 28 years at the DDA, the program has served hundreds of families. It has expanded to two permanent locations and currently supports more than 80 enrolled clients—an all-time high. Still, with a growing waitlist, Rhonda knows there’s an unmet need. When I asked her about the biggest challenges, she didn’t hesitate: staffing and funding. Becoming an interventionist requires a bachelor’s degree in a human behavior-related field such as psychology, social work, or special education. In addition, the State of Idaho mandates 1,040 hours of experience working with individuals with disabilities.

I interviewed one of Rhonda’s long-time interventionists and friends, Lynn Sharp. Lynn’s kids grew up with Patrick, and they were close friends. Speaking about her career at the DDA and working with Rhonda, Lynn recounted, “Progressive knowledge. That’s what this job brought to me, I was always learning something. I loved working with clients because I’d witness their remarkable gifts, and it was a daily reminder of the remarkable.”

Lynn emphasized the impact of local employment opportunities. “I remember early on when I first started working, I took two adults down to the vocational program for work. These clients had never left home, were always with their parents. When they cashed their first paycheck made in their names, it's a joy I’ll never forget. The amount—four dollars.” It’s the kind of impact a business or community can have by providing opportunities for inclusion in their community.

I asked Lynn why people should consider the field. She said, “If you have a genuine love for helping people and for doing it a way where you can contribute directly to the betterment of their lives, this is it.”

“This type of career, it's something you often fall into. And once you do, you love it.”, Rhonda explained. However, Rhonda wants there to be a greater awareness that this career path doesn’t have to be something people stumble upon. She is working on creating more career awareness with local universities. She realizes that Preston might not become home for most people, but even just a few years of working here will give a person significant experience and joyful satisfaction. “Once you are DDA, I tell my workers, you are always DDA,” Rhonda said.

This program wouldn’t exist without Idaho Medicaid, which barely covers the cost of operations, and sometimes, not even that. Upending funding causes anxiety among both Rhonda and the families at the DDA. DDA parent, Paige Haslam stated, “It would wreck their world. They rely on routine and it is how they gain a sense of independence. As a parent, having the extra help is wonderful and allows economic opportunities I wouldn’t have otherwise. Losing these services would be really hard, devastating.”

Rhonda empathizes with this sentiment, remembering her own experience when she lived in Utah. “I really felt like I had access to so few resources. I cannot tell you how grateful I am as a parent and as the director of this program that Idaho’s legislature continues to fund our program.”

When needs arise beyond normal operations, the community consistently steps up. Recently, more than $30,000 was raised to purchase a new bus. A few years ago, the local Elks Lodge raised nearly $20,000 to help the program buy new equipment. During lean financial years, the hospital board stood firm to ensure the program’s survival. It’s a service the community stands behind—and one it continues to benefit from.

A new bus (right) made possible through community donations and state funding.

A new bus (right) made possible through community donations and state funding.

In a recent meeting, Rhonda, now age 71, emotionally announced that she’d be retiring this spring. I wanted to honor Rhonda and her program, so I asked if I could write a story about her. In her genuine humility, she responded, “Is that like really necessary, I mean it’s no big deal.” “Oh, it's necessary,” I said, “And it is most definitely a big deal.”

Over the short time of knowing Rhonda and learning more about her and the program she built, I’ve puzzled together a story of passion and meaning surrounding a person of magnitude. And I have discovered that the one thing Rhonda is truly daunted by is retirement.

When I asked a few clients how they felt about Rhonda’s retirement, their responses were filled with emotion. “I don’t know what to say … I met her when I was nine years old, 19 years ago. She is so much fun,” one said. Another added, “It’s hard for me, but I know she has a family, and I’m excited for her.” A third simply said, “We will keep Rhonda in our hearts forever.”

Rhonda has considered retiring before but never quite brought herself to do it. This time, though, she’s certain. Her kids are asking for a full-time grandma, and she feels it’s time to pass the reins. Still, she assured me her heart will always be in this work. “I’ll always be an advocate—I won’t retire from that,” she said. When I asked her to share the highlights of her long and impactful career, she skipped over accolades, including a lifetime achievement award, and answered through tears: “The staff. The families.”

For anyone wishing to make a tax-deductible donation to the DDA as a gesture of appreciation for Rhonda’s career, Franklin County Healthcare Foundation has set up a special fund:

For credit/debit card donations or other information call: 208-852-4113

Mail checks to:

44 N 1st E

Preston, Idaho

83263

You may also honor Rhonda by writing your local Idaho representative in support of funding that supports the operations of the DDA.

About the author: Jalen Tollefson is the marketing director at Franklin County Medical Center and is a hobbyist writer. For media inquiries, please reach out to marketing@fcmc.org